Stars at Devils Tower. Nikon D750 with a Zeiss 15mm Distagon f/2.8 lens. Ten stacked frames, each shot at 150 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 1600 (1,500 seconds total).

The Conditions

Shooting under moonless conditions can create consistent challenges for astro-landscape photography. The primary challenge is lighting your main subject. When it’s the Devils Tower in Wyoming, you’ve gotta get it right.

Gabe and I were leading a group of eager learners on a workshop a few years ago when I made the above image.

I was not standing at my camera—I was up at the base of the Tower, illuminating it.

So how did we do this?

The Shoot

Well, lemme first show you how it looks without being lit, which you can see in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Nikon D750 with a Zeiss 15mm Distagon f/2.8 lens. 150 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 1600.

It lacked the detail that screams, “Is that the mountain from that famous movie?!?” Right? Yeah.

But one frame did stand out: when some climbers who had to descend after dark illuminated the deep crevices that are the hallmark of this natural stone edifice (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Nikon D750 with a Zeiss 15mm Distagon f/2.8 lens. 30 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 6400.

Aside from that, we wanted more detail in the Tower. So I set my intervalometer to take many, many (infinite, in fact) exposures. (You can read more on how to do that in our post “Mastering the Intervalometer for Night Photography and Long Exposures.”

I knew I intended to make an epic star trail from this. So I aimed for longer exposure lengths of 150 seconds and let the sequence begin. I knew this was still short enough to manage the long exposure noise that the camera would generate in the mid-August Wyoming heat.

I grabbed a two-way radio and drove up to the parking lot. I hit the loop trail and started doing my own lighting. From so far away from the camera, how did I know I was executing the light painting sufficiently? That’s where the radio came in—I kept pinging Gabe to see if my flashlight was providing proper detail and coverage. Trusting Gabe to be the lighting director from the camera position was crucial.

Gabe advised me to cover about one-quarter of the arc around the base of the Tower. We tried a few variations and settled on a final strategy (Figure 3).

Before and after light painting from the base of the tower.

I shot many different variations (Figure 4) through the evening, sometimes re-framing, sometimes adjusting the exposure length. Even when you’re confident about your approach in the field, it’s always good to push the boundaries of your decisions and to give yourself more options to look at when back at the computer.

Figure 4. The different strategies I shot that night gave me lots of options to choose from in post.

The Post-Production

The final set of frames I chose to work with is this:

Figure 5.

Each image required a gradient for the sky, and a proper Range Mask set to 28/100 Luminance and 19 Smoothness. I also used the mask brush to remove the gradient from Devils Tower itself and from the trees below.

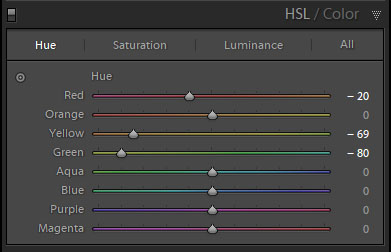

Once the mask was done, I made the adjustments, which were intended to emphasize (but not over-process) the sky. Sometimes that’s a fine line, and one we always want to be conscious of. You can see the mask I created in Figure 6, and the adjustments in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Then I needed to stack the frames in Photoshop. In several previous How I Got the Shot blog posts we’ve discussed stacking frames to create star trails and to combine different light-painted compositional elements into one image. This time I used the same technique to achieve both those goals in one photograph—i.e., to get the stars to trail and the light-painted sections of the Tower to composite.

The process is:

Select all the pertinent frames in Lightroom by shift-clicking the first and last.

From the menu, choose Photo > Edit In > Open as Layers in Photoshop.

Once the image opens select all the layers by clicking on the top layer, pressing the shift key and then clicking on the bottom layer.

In the Blending Mode dropdown above the layers (the box that defaults to saying Normal), choose Lighten.

Save and close, which will bring the stacked image back into Lightroom where you can make final edits.

I was really pleased with the stacked result:

Nikon D750 with a Zeiss 15mm Distagon f/2.8 lens. Ten stacked frames, each shot at 150 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 1600 (1,500 seconds total).

The photograph has more mystery with the tree line falling into silhouette and the Tower having detail. This emphasizes where the viewer should look.

A Little Cleanup

Due to some people’s red headlamps and flashlights, the trees and ground closest to us picked up the color. It’s quite hard to edit away, so I brushed in some local adjustments subtracting highlights and whites. After stacking, that still wasn’t enough, so I ended up using layer masks to eliminate the distracting details.

(Hmmmm. Come to think of it, it may have been the brake lights of my rental car when I returned to the group. D’oh! And possibly a “mea culpa” moment. Whoops. Bad Matt.)

When I re-edited the stack this time, I noticed something new. I wanted to crop it to a vertical. It felt … more powerful. More focused.

The final, final result:

Nikon D750 with a Zeiss 15mm Distagon f/2.8 lens. Ten stacked frames, each shot at 150 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 1600 (1,500 seconds total).

Wrapping Up

I gotta say, I am excited to return to the Devil’s Tower with Chris later this year. It’s going to be amazing. What will he and I dream up together? And what will the workshop participants dream up? I bet it’ll be out of this world. (Yeah, I went there.)

How do you achieve better astro-landscape photography by collaborating with friends and peers? Tell us more in the comments, and show us photos!

Note: Want to join Matt and Chris to make epic night photography images at Devils Tower National Monument? We have two spots left for the workshop, so sign up now!