Lassen Volcanic National Park. © 2018 Chris Nicholson. Nikon D5 with a Nikon 14-24mm f/2.8 lens, light painted with a Coast HP7R flashlight. 25 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 6400.

The Location

Last summer, Lance and I visited Lassen Volcanic National Park to shoot for a few days (er, nights). For both of us, it was our first time there, and we quickly discovered that this Northern California wilderness is one of the best kept secrets of the national park system. The scenery is beautiful, bewildering and varied: volcanoes of different types and shapes, snowcapped peaks, reflecting lakes, babbling brooks, lush meadows, multicolor pumice fields, steaming geothermals and more await photographers and their cameras. Not to mention … deliciously dark skies.

On our second day in the park, we stopped at a visitor center to talk to a ranger about possible places to photograph in the dark. She gave us a lot of great information, including an auto-tour map with suggested sites to see, and she marked the areas that she thought would be of interest to us. We ventured out for our daytime scouting, driving the main road (the aptly named Lassen National Park Highway), hiking short trails, making daytime photos (gasp!) and all-in-all enjoying the experience of being in the outdoors in such a captivating space.

Along the way we stopped at a trailhead parking lot that afforded a 360-degree view of mountain peaks and valleys, all with great visual lines to the sky above them—i.e., no trees, cliffs and so on that would block our sky views in any direction. In other words, it was a perfect place to set up for a night shoot. And then we spotted what turned out to be the star of the scene: a massive boulder perched at the edge of a cliff.

A scouting photo of the boulder.

We were both pretty excited about the rock as a subject, as it has an interesting shape, is in an interesting place visually, is in front of an interesting background from all available angles, and we could safely set up and shoot from about 180 degrees around it. In other words, this was going to be a lot of fun.

Moreover, because the cliff faces south, we knew we could get the Milky Way galactic core in the composition. So we pulled out PhotoPills to see exactly when and where the Milky Way would appear, planned our shots, and then continued exploring the park with the knowledge that we would definitely return to this spot after sundown.

The Shoot

We arrived back at our shoot location early in twilight—so early that we couldn’t see the Milky Way yet, but that was fine because we were surrounded by many other creative opportunities. Lance ventured a little east on the cliff edge to work on a separate idea with a twisted tree, and I stationed a camera at the far end of the parking lot to rip some longish exposures over the mountain ridge to the west (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Star trails over a Lassen ridge. Nikon D850 with a Nikon 80-200mm f/2.8 lens. 6 minutes, f/6.3, ISO 64.

As the sky grew darker, I started working with the boulder. The Milky Way was not yet apparent in the sky, so I worked on some alternative compositions with the mountains in the background, using the silhouette of the distant ridge as a leading line into the rock (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Nikon D5 with a Nikon 14-24mm f/2.8 lens. 15 seconds, f/8, ISO 4000.

Once I was done with that, I looked south, and there it was: the galactic core rising over the valley. So I repositioned my camera and tripod to start working on the photo I was there to create.

The valley below the cliff is a scenic wonder in daylight (in moonlight too), but in pitch-dark it was just vast blackness—so I lowered my tripod to get it out of the frame (Figure 3). The real stars of the composition were the Milky Way and the boulder.

Figure 3. Working on the composition, but with a poor-choice white balance of Daylight.

I worked the composition a little more, and then changed my white balance. I’d been using Daylight during the blue hour portion of the shoot, but once the sky darkened, I wanted a white balance that would help the sky look more like “night” and that would also help draw out the delicate colors of the Milky Way. So I switched the white balance of my D5 to manual and dialed it in to 3800 K (Figure 4). (For more on this, see Matt’s blog post “How to Choose the Right White Balance for Night Skies.”)

Figure 4. White balance at 3800 K.

At this point you can see that Lance was in the background doing his light painting on a different subject. This didn’t bother me. First, I was only making test shots. I didn’t care about someone else’s light; I cared only about the specific elements that I was testing for, i.e. composition, focus, exposure, white balance, etc. Second, once I was ready to start executing my “real” image, I knew Lance and I could communicate and take turns light painting our different setups, and that when his flashlight was off, he and his camera would disappear into the shadows.

For focus, a quick check of a hyperfocal distance chart confirmed that I could lock in on the boulder and still have the stars sharp. So I shined my Coast on the rock and auto-focused. Easy peasy.

The exposure was pretty simple too. I knew I wanted sharp stars for a sharp Milky Way. Using the 400 Rule with a 14mm focal length, that gave me a top shutter speed of 25 seconds (400 / 14 = 28.57, rounded down to 25 for safety), which I shot at f/2.8 and ISO 6400.

Then I started working on the light painting. Using a Coast HP7R flashlight with a homemade color-warming filter, I worked from the left of the frame. I chose this angle for three reasons:

Working from the right was nearly impossible because of the cliff drop. I could have done it if I learned how to fly, but I didn’t have time for that in the middle of the shoot.

When light painting, I usually want the direction of the added light to “make sense” visually, to almost look like the illumination could be coming from something else in the scene—in this case, the galactic core. Of course no one will think that the Milky Way was actually bright enough to illuminate the boulder, but I find that the visual suggestion of it works better.

When light-painting a subject on the right side of the composition, I usually like to have the light coming from the left, across the majority of the frame. (And vice-versa for a subject on the left.) If I’d painted from the other side (Figure 5), then the brightest, highest-contrast parts of the boulder would have been way over on the right edge of the frame, separated from the secondary subject of the image (the Milky Way) by a large shadow. That would have been far less compositionally effective. (This is a personal guideline, and an effective one. But it’s not a rule. In fact, you can see that I went against this guideline in the image above of the boulder without the Milky Way.)

Figure 5. I moved as close to the edge of the cliff as I could to light paint from camera-right, and the result proved the efficacy having the light come across the majority of frame. Also, it was nearly impossible to paint from that angle without having the light hit the sapling too.

The final step was just a matter of playing around with the light painting, trialing-and-erroring, repeatedly coming back to the LCD to review my results. I was evaluating factors such as:

how out far out of the frame I needed to stand so the camera couldn’t see the flashlight

whether to use direct light (harder, more contrast) or reflected (softer, less contrast)

which angle to paint from to create the most texture

which angle would illuminate enough of the boulder to be interesting but not so much that I was light painting everything (which is boring)

which angle accomplished all that without lighting the sapling to the right of the rock, which I deemed a compositional distraction

how long to keep the light on so the boulder would be bright enough to draw interest yet subtle enough to not be garish or overwhelming

Failed iterations of my light painting approach. Or, rather, honing by trial and error.

Once I’d made all of my decisions, I was ready to make the final photograph. By that point Lance had joined me at the boulder, and we took turns light painting our individual setups. Again, the key was communication, so that we didn’t inadvertently ruin each other’s images—each of us asking if the other was in the middle of an exposure before turning our flashlights on.

I loved how everything came together. One of my field rules is that when I finish executing my idea, before changing the setup I always try something I wasn’t planning, just to push myself out of the immediate box and see if I stumble across a great idea. In this case, I tried backlighting the rock (Figure 6). I hated it—so I moved on. …

Figure 6. The failed backlighting idea.

Incidentally, while I was doing all of this, I still had my second camera, a D850, capturing star trails from the top of the hill, creating the image in Figure 7. That’s a great use for having two cameras in the field—one for long exposures and one for doing other work during the wait.

Figure 7. Star trails over Lassen Peak. Nikon D850 with a Nikon 80-200mm f/2.8 lens. 13 minutes, f/2.8, ISO 160.

The Post-Production

This particular photography didn’t need a lot of work in post.

I cropped out the bright star that was sitting immediately on the right edge of the frame, where it served as only a visual distraction, pulling attention far away from both the primary and secondary subjects.

Using the Spot Removal tool, I cloned out a patch of snow that was picking up just enough light to be seen in the background, as well as one bright and three faint plane trails (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

I boosted Exposure (+20) and Whites (+34) to increase overall brightness, then Clarity (+19), Dehaze (+24) and Vibrance (+8) to add some punch to the sky (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Usually I’ll go over the galactic core with a custom Milky Way brush, but I didn’t think this image needed it. Sometimes not doing something is the best decision.

Figure 10.

The Final Adjustment

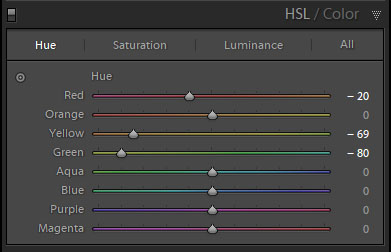

The last correction was one I couldn’t make by myself. The combination of using a CTO filter and shooting with a white balance of 3800 K made the light kind of green. I’m red-green color blind, so I asked Tim if he’d be a second (better) set of eyes while I tried to get the color of the rock accurate. Using the targeted adjustment tool in the Hue section of the HSL panel, we clicked a green sample in the rock and dragged down, which brought the Yellow slider to -69 and the Green to -80. The rock was then a little too warm, so we manually pulled Red down to -20. (Figure 10.)

There are two lessons here:

Knowing how to work around your limitations can be critical. Much thanks to Tim, my sister Ann and several past girlfriends for helping me color-correct through the years.

In the field, knowing my limitations and when shooting at a non-Daylight white balance, I should have used a Luxli Viola LED panel for the painting. Why? Because that would have allowed me to dial in the color temperature of the light to 3800 K or slightly warmer—then I would have known the color was accurate even if I can’t see it. (Another way to do this is to use a combination of color-correcting gels to alter the Coast’s output accordingly. Check out Tim’s post “Level Up With Light Painting: Correcting the Color of Your Flashlight (Part II).”)

Figure 11. The final image.

Wrapping Up

I finished my photo before Lance finished his. I tooled around with a few other image ideas in the same area (Figures 12 and 13), but soon settled on light painting Lance while he worked, creating a portrait of one night photography’s true masters in his element (Figure 14). By this time the moon had risen, which illuminated the valley in the background, adding more of a sense of place to the scene.

Figure 12. Tail end of the Milky Way over Lassen Peak. Nikon D5 with a Nikon 14-24mm f/2.8 lens. 20 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 8000.

Figure 13. Milky Way disappearing in the moonrise. Nikon D5 with a Nikon 14-24mm f/2.8 lens. 25 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 6400.

Figure 14. Lance at work. Nikon D5 with a Nikon 14-24mm f/2.8 lens, light painted with a Coast HP7R flashlight and a Luxli Viola LED panel. 25 seconds, f/2.8, ISO 6400.

Afterward we moved on to our second shoot location of the night, a placid alpine lake just up the road, where we ripped some long exposures of star-circle reflections above Lassen Peak.

Lassen Volcanic is truly an extraordinary national park. I have no idea when I’ll be back, but the day I am can’t come soon enough.

Want to explore Lassen Volcanic with Lance and Gabe on an epic night photography adventure workshop this August? Sign up here!