Light painting can be fun, creative and rewarding, but also one of the most challenging aspects of night photography. Carefully crafted light painting can make the difference between a boring and a spectacular image. The range of tools and techniques we have at our disposal make for unlimited possibilities. Effects can range from subtle (from simply filling in shadows to manage contrast and exposure) to dramatic and bold (highlighting a subject in a way that only light can do).

The full moon is rising behind the vertical car. The bus has a Luxli Constructor light on medium power inside at ground level and facing toward the back of the bus. The car in the foreground does not have any added light. The backlighting from the moon created strong shadows and a glow in the sky around the car. All three variations 20 seconds, f/6.3, ISO 3200 with a Nikon D750 and Irix 15mm f/2.4 lens.

Even a quick pass of a Surefire P6 from camera-left was too much light because of the high ISO.

In the final version, I bounced the light from a Surefire P6 off my hand held over my head while standing about 6 feet to the left of the camera. It was enough to subtly light the car in the foreground while preserving the shadows and overall feel of the image.

The first step to light painting is to figure out what you want to light, and what you are trying to achieve by lighting it.

Once you have that down, the next step is to determine the amount, color and quality of light required. There are lots of decisions to be made, and the answers are different for every image and every situation:

- Are you lighting multiple objects or multiple surfaces?

- Do you need to illuminate from multiple positions?

- Do you want soft, diffuse light or contrasty directional light?

- Should you use light that matches or contrasts the color of the existing light?

The remainder of this article assumes that you have gotten to this point, and are ready to take it to the next step.

The last-quarter moon was just rising behind camera to the right. Lit with a Surefire P9 incandescent flashlight from the left and right sides at oblique angles. It was a challenge to light both sides of this large building in 30 seconds, but it was freezing cold so I ran from side to side to do the lighting to keep warm. You can see that I overlit the right side and the underside of the top of the building. The background was too dark. 30 seconds, f/8, ISO 800. Canon 6D and Nikkor 28mm f/3.5 PC lens.

After several attempts, I conceded that I would need to use a longer shutter speed, both to add more exposure to the background and to do a better job at the lighting. The light painting is more evenly distributed, and I added light to the foreground. Additionally, the longer exposure opened up the inside of the store, which is lit by vintage, very orange Edison bulbs that have been burning continuously for decades. 75 seconds, f/8, ISO 800. Canon 6D and Nikkor 28mm f/3.5 PC lens.

Controlling the Look

Learning to control lighting ratios between the existing light and whatever light you bring to the party is one of the most powerful ways that you can influence the overall look of your images.

If you are not sure what I mean, think of it in terms of a rudimentary on-camera flash. If you use flash on a point-and-shoot camera, or even a DSLR in “P” mode indoors at night, you’ll end up with a foreground that is properly exposed, and a background that is likely to be dark and underexposed. You can adjust the flash compensation to reduce the amount of flash relative to the existing light for a better balanced overall exposure. Another way to achieve the same end would be to increase the exposure time to increase the background exposure.

“The more light you add to your subject relative to the ambient light, the more your illuminated subject will stand out from the background.”

We can do that same thing in the field with light painting. But it takes a bit of work, and a clear idea of what we want to say with our images.

It’s all about the context. If your added light is two or three stops darker than the existing light, it will be barely noticeable. If it is two or three stops brighter, the more pronounced and dramatic it will be.

In the simplest terms, the more light you add to your subject relative to the ambient light, the more your illuminated subject will stand out from the background. Within the parameters of a workable exposure, exactly how much light to add compared with the ambient light is a matter of taste, and is one of the ways a night photographer can style their images.

Case Study: Mono Lake Series

The exposure for all five images is 20 seconds, f/4, ISO 12800, and they were shot with a Canon 6D and Nikkor 28mm f/3.5 PC lens. Starlight conditions with practically no light pollution.

Starlight only.

Very low power, broad-beam LED flashlight from camera-right for 2 seconds.

Bright LED flashlight from camera-left for shortest possible time. The brightness of the light meant that I had to use it like a flash by waving it in and out of the scene as quickly as possible. It was impossible to control the light with any consistency.

Very low power, broad-beam LED flashlight from camera-left and right for 3 seconds from each side. I liked the look, but wanted to try a warm light that would contrast the cool, blue sky.

Very low-power, incandescent flashlight from camera-left and right for 1 second from each side. This light was brighter, and therefore harder to control at ISO 12800. It was also less diffuse, which made it difficult to light the formation with just a single 1-second pass of the light from each side, but it was my preferred result.

Arriving at a Ratio

How, though, do you decide how much light to add in comparison with your ambient exposure?

There are two main ways to vary the lighting ratio:

- Just as in the flash example above, you could increase or decrease the amount of added light. This can be achieved with a brighter or dimmer light source, or by using a continuous light for a longer or shorter period of time, or by popping a flash once or multiple times.

- Extend or shorten the exposure time. Assuming that you used the same amount of light painting, the length of the shutter speed would affect only the ambient exposure. (Whereas changing either the ISO or the aperture would affect both the existing and added light. Our goal is to separate the ambient and added light, not to adjust them proportionally.)

To summarize, you change the lighting ratio by increasing or decreasing the amount of added light, or lengthening or shortening the overall exposure time without changing the added light. Use whichever method works better for each particular shot.

Controlling the Light

You can control how much light you add in different ways depending on the painting tool you’re using:

- If you are using flash, or a variable brightness continuous light source such as our beloved Luxli Viola, you can increase or decrease the intensity.

- With a flash, you could also use multiple pops of light, and each additional fire doubles the amount of light on your subject.

- If you are using a flashlight, then you can increase or decrease the amount of time you employ it to light your subject, provided that time fits within your exposure length. (Increasing the exposure time without altering the added light painting will reduce the ratio—and therefore the impact—of the light painting. Reducing the exposure time without altering the light painting will make the light painting stand out more.)

- In some situations, of course, you may need to adjust both the added light and the exposure time to find the right combination.

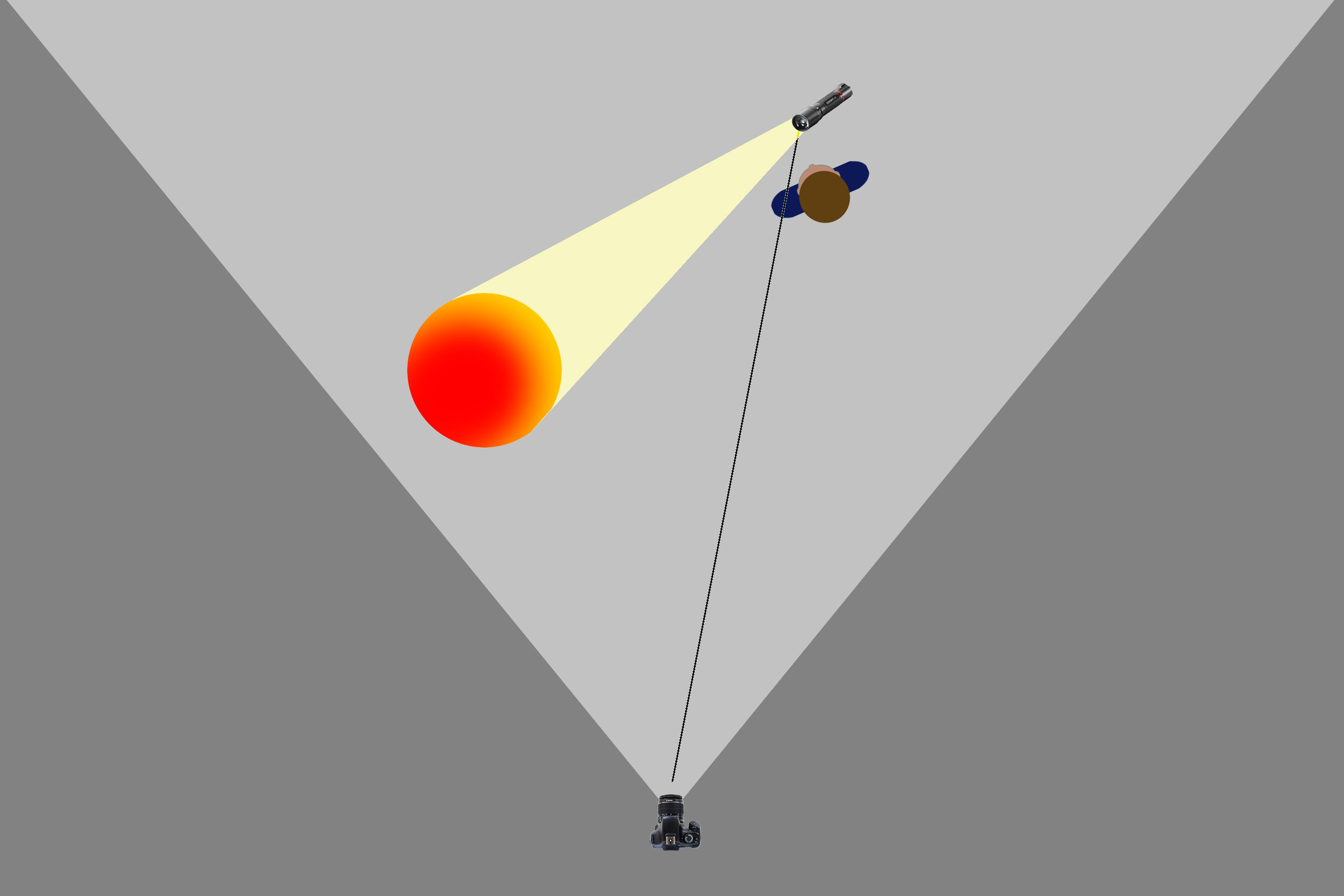

- One other way to modify your light painting is to increase or decrease the distance between your light source and your subject, keeping the Inverse Square Law in mind. The Inverse Square Law essentially states that doubling the light-source-to-subject distance results in one-quarter of the light reaching the subject.

Case Study: Trona Series

From my “Loos With Views” series. A nearly full moon, with light pollution from Trona and Ridgecrest in the background.

The first attempt. 30 seconds, f/4, ISO 800. Canon 5D Mark II with an Olympus Zuiko Shift 35mm f/2.8 lens. Incandescent flashlight from the right, and inside the loo. I considered this to be overlit.

The second attempt. 30 seconds, f/4, ISO 800. Canon 5D Mark II with an Olympus Zuiko Shift 35mm f/2.8 lens. Incandescent flashlight reflected off my hand from camera-left, and LED bounced off the back wall of the structure. The LED was too harsh, and I didn’t want to see the signage on the front.

The third attempt. 30 seconds, f/4, ISO 800. Canon 5D Mark II with an Olympus Zuiko Shift 35mm f/2.8 lens. Better-controlled LED bounced off the back wall of the structure, and no light on the front.

The final attempt. 10 minutes, f/4, ISO 100. Canon 5D Mark II with an Olympus Zuiko Shift 35mm f/2.8 lens. A few seconds from camera-far-left with a Surefire P6 incandescent flashlight to show texture in the structure. I used the same light for a few seconds inside the loo, bounced off the front wall. The light on the rock and the vent pipe was ambient that accumulated during the long exposure. The color of the sky is so different due to the combination of the long exposure and the moonlight’s effect on the white balance.

Complications

Other constraints (such as shooting at high ISOs to avoid star trails) may come into play, and these can complicate things further.

A common scenario when light painting at high ISOs to preserve star points is that a light source may be so bright that a fraction of a second is all that is required to light a scene, making it next to impossible to control the light well. Reducing the camera exposure would have a negative impact on the stars, and would also even further reduce the amount of time available to get into position and execute the lighting.

In that case, using a dimmer light source is the best option. If the location is treacherous and getting into position takes some time, two good strategies are setting a delay on the exposure or triggering the shutter remotely once you get into position.

Conversely, when working under the light of a full moon, a longer duration of light painting is a good way to increase the added-to-existing light ratio. In urban environments with a lot of ambient light and relatively short exposure times, utilizing a brighter light source might be the best approach.

But It’s Really Not Complicated

In any case, some thoughtful examination of the situation and available options will go a long way toward achieving the desired look.

If after reading this you are thinking about going back to daytime photography, please know that these decisions and tactics are really not that complicated. I don’t know anyone who does mathematical calculations in the field to figure out their light painting—at least no one who has done it more than once!

Like everything related to night photography, it’s a mélange of art and science that can be mastered only by trial and error, accumulating knowledge and experience along the way.