Moon Over Alabama Hills. Nikon Z 6 with a Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 lens, light painted with a Luxli Viola. Two stacked frames shot at 5 minutes, f/8, ISO 200 (foreground) and 10 seconds, f/8, ISO 6400 (sky).

The Location

Alabama Hills National Scenic Area encompasses a range of rock formations to the east of California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains. It’s a huge draw for people with cameras of all sorts. Television and movie productions—especially Westerns—have been filmed there since the 1920s. Photographers have been going there since landscapes were a thing to shoot. And night photographers (light painters in particular) love the rocky scenery and the very dark skies.

Mobius Arch, Alabama Hills. A great example of the area’s fantastical scenery. Canon EOS-1DS with a 16mm lens. 1/90, f/13, ISO 100.

The Moon

For many, the moon is an unwelcome addition to our night sky. Its presence makes nighttime landscapes look like day, overpowers the Milky Way and obscures all but the brightest stars. But while initially the moon may seem like a problem, it can also provide opportunities for other styles of night photography. In addition, embracing moonlight will expand your shooting time to more than just the one moonless week every month.

One aspect of shooting with the moon present is accepting you’ll have fewer stars in the sky. That’s OK. You can create star-filled skies later in the month, during a new moon. Brighter moonlit situations give us a chance to put more emphasis on the landscape instead of the sky.

Begin by choosing compelling subjects that you might photograph during the day. For example, I’ve always been fascinated by the metamorphic rock found throughout the Alabama Hills in the High Sierra. In this image I really wanted to emphasize both the texture and the gentle curves of these magnificent formations. Last month’s waxing gibbous moon provided exactly this opportunity.

The Ambient Exposure

My goal was to accentuate the foreground shapes and to have the moon render like a starburst. So first (as usual) I began by using ISO 6400 for a series of test shots. This allowed me to fine-tune my composition and to determine my base (ambient) exposure of 10 seconds at f/8.

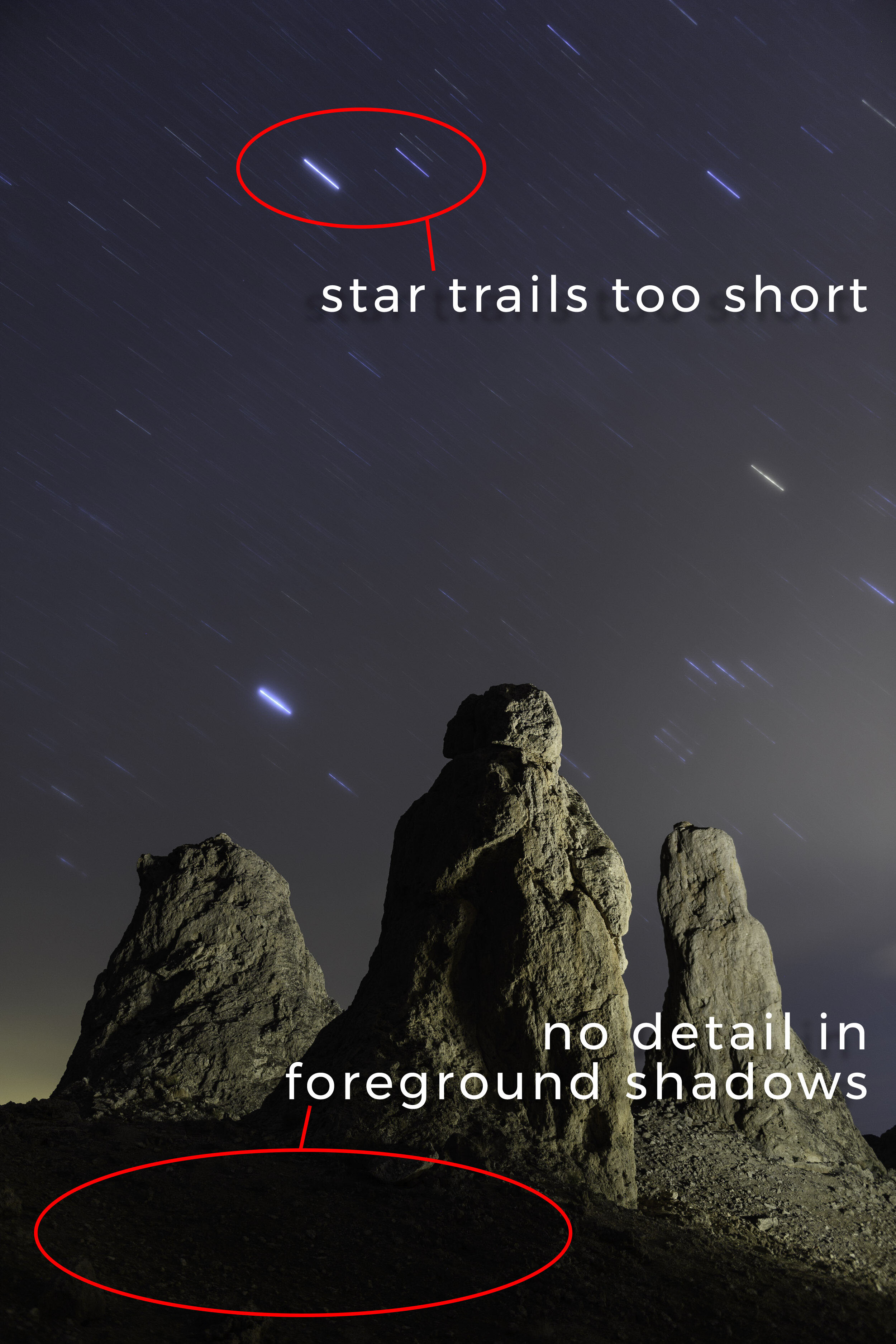

This exposure was short enough for the moon to remain round and for the stars to render as dots rather than dashes (Figure 1). Also, using a 24mm wide-angle lens allowed me to create a starburst effect without having to stop down too much (the longer a lens is, the more you need to stop down to create the star effect).

In short, 10 seconds, f/8, ISO 6400 was a perfect exposure for the sky, stars and moon.

Figure 1. The relatively short exposure kept the moon round and the stars sharp. A longer exposure would have had the opposite affect: The moon would have become oblong and the stars would have begun to trail.

The Light Painting

Once the ambient exposure was established, I began looking at how the light was illuminating my foreground. The full moon over this small cliff face created the perfect backlighting to accentuate the curves and texture of the foreground rocks. However, it also put the entire cliff face into shadow.

To fix this problem I placed a tripod with a Luxli Viola light panel just off camera-right, about 30 yards in front of me. This placement provided texture-revealing sidelight on the cliff face and helped fill in the foreground shadow (Figure 2).

The next step was to balance the Viola with the moon. I began by setting the panel’s brightness to 25 percent. But … oops! That made the image look fake, as the exposure on the back wall was way too bright. I lowered the setting to 12 and shot again, which provided just the right amount of light to make the scene somewhat more believable.

Figure 2. The sidelight from the Luxli Viola brings out the texture in the cliff face.

The Color Temperature

The next problem to solve was the color. For most night photography (including moonlit scenes) I set my camera’s white balance to 3800 K. This renders the sky to my tastes. Remember though, white balance is quite subjective. Some folks like night skies to appear more blue, while others like a more neutral sky. There is no right or wrong. You should always consider white balance suggestions as a starting point.

Because I was using a camera white balance setting of 3800 K, I set my Luxli’s color temperature to 3800 K to match. After a couple of more test shots I realized that this setting made the added light a bit warmer than the moonlight that was kissing the foreground. Increasing the Luxli’s color temperature to 5500 K better matched the color of the moonlight, which made the whole scene appear a bit more natural.

The Final Frame

I had shot all my test frames with an ISO of 6400 to shorten the time between tests. But while ISO 6400 was great for the sky and testing, I wanted a higher-quality, lower-ISO exposure for my foreground rocks. For this I turned to the Six-Stop Rule.

The Six-Stop Rule is a shortcut to translate a short, high ISO test exposure into a longer, low ISO exposure. The rule is simple: The amount of seconds it takes to create a good exposure at ISO 6400 equals the number of minutes at ISO 100. For example, 10 seconds, f/8, ISO 6400 equals 10 minutes, f/8, ISO 100. Both of those exposures allow the same amount of light to hit the sensor.

In this case, I didn’t want to wait 10 minutes, so I used an equivalent exposure of 5 minutes, f/8, ISO 200. Using this exposure didn’t change anything about the lighting. Because both the moonlight and the Luxli are constant light sources, lowering the ISO and lengthening the shutter speed provided identical exposures where the light level looked exactly the same. The only difference, of course, was that the longer exposure showed movement in the stars and moon.

Putting it All Together

The final image. Moon Over Alabama Hills. Nikon Z 6 with a Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 lens, light painted with a Luxli Viola. Two stacked frames shot at 5 minutes, f/8, ISO 200 (foreground) and 10 seconds, f/8, ISO 6400 (sky).

Many times the final image comes together with advance knowledge of how you’ll proceed, while other times the creation process evolves during the process. In this case, a bit of both happened.

I knew I wanted to use the moon as the main light to accentuate the foreground rocks and also to create a moon star and keep the stars sharp. I achieved that through the initial ISO 6400 test images. During those tests, I realized that I needed to add some fill light to the back wall in shadow. So out came the Luxli light panel. Setting the light panel to the same color temperature as my camera produced a warmer light than the moon was providing, so I upped the K setting to 5500.

After lowering the ISO to create a higher-quality rendering of the rocks and wall, the last step was in Photoshop: A simple layer-and-mask blend of the foreground and background.