Note: This is the second in a three-part series about one of the most common questions we get: How do you deal with light pollution? We have three answers: with filters, with post-processing, with creativity. In this week’s blog post, Lance Keimig discusses the second of those solutions: processing in Lightroom.

Last week, Matt wrote about his experiences testing a couple of light pollution filters, and he showed how they can be useful for neutralizing color casts in clouds from artificial lights, in reducing atmospheric haze, and especially for taming the beasts known as sodium vapor lights.

He showed that the two filters he tested work primarily by filtering out a narrow band of intensely orange light that is particular to sodium vapor lights. Before the widespread adoption of LED street lighting, high pressure sodium vapor was the most common form of street lighting used worldwide. These lights are still quite common, and until they are eliminated altogether, light pollution filters will probably be the first line of defense against the color shifts they cause in photographs.

The image above is a good example of the types of artificial light sources that cause light pollution. The intensely yellow lights are low pressure sodium vapor, and the others in the scene are high pressure sodium vapor. Canon EOS 6D with a Nikon 28 mm f/3.5 PC lens. 6 seconds, f/8, ISO 200.

When we consider the problem of light pollution in night photography, there are two conundrums:

unwanted color casts in the clouds and in the sky

stray light that obscures the stars in our images

Light pollution filters can address both of those issues, providing that the bulk of the light pollution is from sodium vapor lights.

However, if you don’t use a light pollution filter, post-processing offers an alternative method to correcting unwanted color casts from light pollution in night photographs. In this post and the accompanying video (you can jump to it here), I’ll show you examples of how you can employ post-processing techniques to minimize unwanted color casts from light pollution. All of these examples utilize Lightroom Classic’s White Balance, Hue, Saturation and Luminance (HSL) and local adjustment tools to achieve the desired effects.

The first example (Figure 1) is one that I made last year during our Shi Shi Beach adventure in Olympic National Park. In this case, the lights from Victoria on Vancouver Island reflected off the low cloud cover and turned the sky yellow. A simple white balance adjustment took care of the yellow, and then a little HSL work with the targeted adjustment tool helped with the red and magenta from the beacon on the hill. I could not remove all of the red and still have the image look natural, so I just toned it down a bit.

Figure 1. Light Pollution over Vancouver Island. Nikon Z 6 with a Nikon Z 24-70mm f/4 lens. 693 seconds, f/5, ISO 800.

I made the next image (Figure 2) at the Owens Valley Radio Observatory in California. Light pollution on the horizon to the south shows a yellow glow from sodium vapor lights. HSL adjustments took care of removing the unwanted yellow from the image.

Figure 2. ORVO and Milky Way. Canon EOS 6D with a Nikon 20 mm f/3.5 AIS lens. 20 seconds, f/4, ISO 6400.

The image from Lassen Volcanic National Park (Figure 3) also had yellow light pollution at the horizon, but also a fair amount of yellow and orange in the soil at the foreground, so an HSL adjustment would have affected more of the image than needed. In this case, I used a local adjustment brush and desaturation to solve the problem.

Figure 3. Cinder Cone, Milky Way, Jupiter, Saturn and Mars. Nikon D750 with an Irix 15mm f/2.4 lens. 25 seconds, f/3.2, ISO 6400.

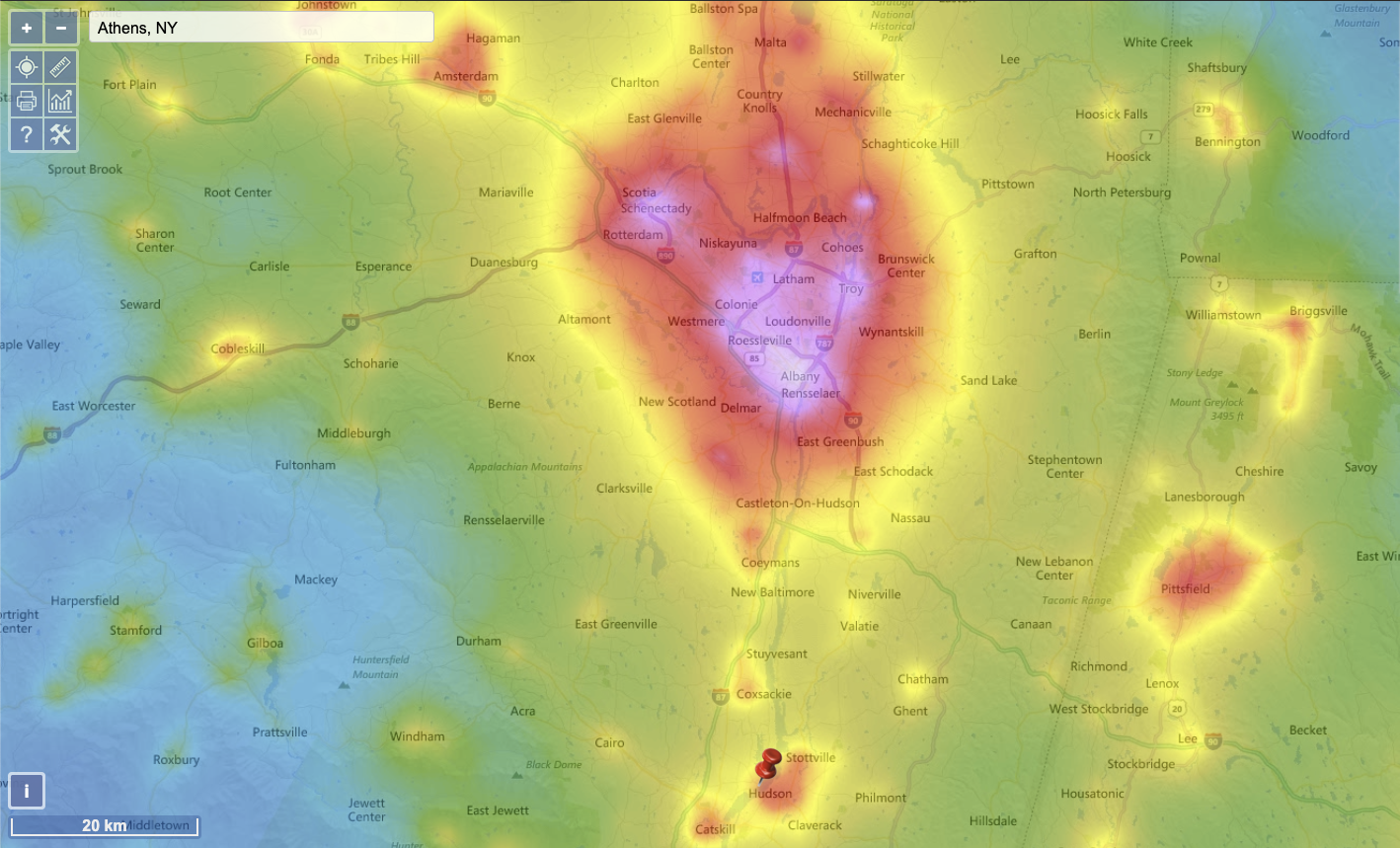

Dealing with light pollution in urban environments tends to be a bit more involved, and also subject to taste in how the image is presented. Below are two examples from Lowell, Massachusetts, an environment primarily lit by sodium vapor with a host of other light sources thrown in for good measure. For this first one (Figure 4), I used a gradient on the sky to remove the color cast without affecting the foreground.

Figure 4. Lawrence Mills, Lowell, Massachusetts. Canon EOS 5D with a Nikon 28mm f/3.5 PC lens. 74 seconds, f/8, ISO 100.

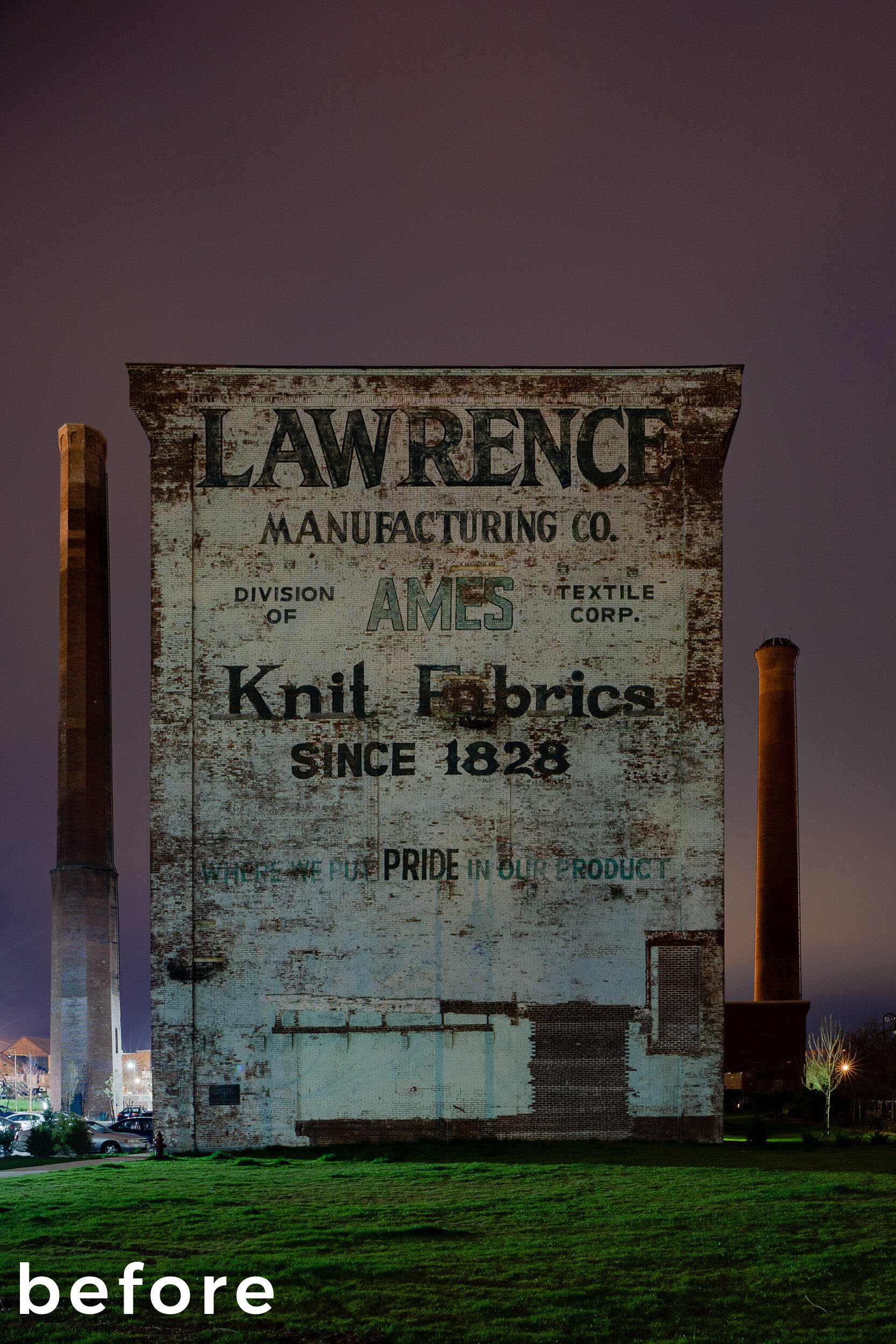

In this last example (Figure 5), setting the white balance by using the eyedropper on the clouds eliminated the color cast from the ambient sodium vapor lights, but exaggerated the cyan from the metal halide lights on the structure. A selection with the local adjustment brush enabled me to desaturate the cyan on the building without affecting the rest of the image.

Figure 5. Lawrence Mills, Lowell, Massachusetts. Canon EOS 5D with a Nikon 28mm f/3.5 PC lens. 73 seconds, f/8, ISO 100.

Video Tutorial

In the video below, I offer more detail on how I accomplished the edits I mentioned above, walking you through all the steps for achieving the same results in your own photos affected by light pollution.

Wrapping Up

As you can see, if you don’t have a light pollution filter, or even if you do, post-processing techniques offer another option for dealing with light pollution in nocturnal images. The techniques are most effective at minimizing color casts from gas discharge lights such as sodium or mercury vapor, or metal halide lights.

However, be aware: If the stars are obscured by scattered light in the atmosphere and are thus not recorded by the sensor, no amount of post-processing can bring them back. However, judicious use of the Dehaze slider will help bring out the stars that are present, and can also compensate for the loss of contrast from light reflected off of particulates in the low atmosphere that are the source of the problem.

In Part 3 next week, Chris will write about learning to live with light pollution in night images, and how to turn a hindrance into an unexpected bonus. Stay tuned, as the more tools you have at your disposal, the better your chances of a successful image regardless of the light conditions!